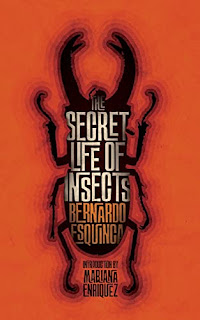

9781956321953

Valancourt, 2023

translated by James D. Jenkins

illustrations by Luis Perez Ochando

198 pp

hardcover

I initally came across the work of Bernardo Esquinca in the first installment of this publisher's Valancourt Book of World Horror Stories. His story "Señor Ligotti" was a standout in that book, so when Valancourt announced the publication of an entire volume of this author's work, I was elated.

This book ticks every box I have as a reader of the weird and the strange. There are no cut-and-dried solutions to the mysteries the author offers, leaving the stories on the open-ended side of things and allowing the reader's imagination to kick in and ponder the implications of what he or she has just read. Many times, for me anyway, that's when the actual horror of the sitution creeps in, continuing to linger with me long after turning that last page. In Esquinca's words, as quoted in the introduction by Mariana Enriquez, ..." the best stories are like abandoned houses that nobody wants to stay in, but which you can't stop thinking about after spending a night in them." That is exactly what you get here.

All of the stories included here are terrific, but as usual, I have favorites. At the top of my list is "Pan's Noontide," which seamlessly blends together crime fiction, horror, mythology, modern environmental concerns and greed-based corruption to create an unforgettable tale. Maya, a woman with a failing marriage, has strange dreams, which she knows the psychiatrist she's seeing completely misinterprets. At some point in the therapy, she realizes that the dreams are no longer nightmares but rather "a call." In the meantime, her husband, a specialist in "classical mythology and ancient folklore" at the local university, has been called by an officer in the Homicide Division to assist him with what he believes is a "ritual killing" of a forest ranger. He needs Arturo's help to discern from photographs he has whether there might be "some symbolism" that might offer a lead or whether the police are simply "dealing with a psycho who thinks he's a conceptual artist." Right away Arturo realizes that the pictures reflect a "clear reference to the god Pan," but he doesn't understand why the forest ranger was a target since Pan was a "protector of nature." He also realizes that he's seen something like this before, and had just brushed it off. This time around, he's definitely interested. There are times when the author writes with a sort of Russian doll effect, with a story nestled inside of another story that in this case, can take you somewhere else altogether. "Dream of Me" is a perfect example of this type of construction, highlighting another theme that is prevalent throughout this book, echoes of the past that find their way into the present. The story revolves around a doll named Greta, sent by someone unknown and handed to the narrator by a detective who had been tasked to deliver it. Evidently this was highly unusual, since finding his dolls was something done personally by the narrator, complete with "verifiable story behind it." The detective knows only that he had received an anonymous phone call with instructions to track down the recipient, Daniel Moncada, who notes that it "is the first time a doll has come to me without my having to track it down." He offers the detective double his fee to find the anonymous caller. In and around the mystery of Greta's origins, we get a peek inside of what appears to be Moncada's doll files. It's not so much the dolls that are the focus of these stories, though, but rather the broken people who had owned them. I have to say I tend to run from creepy doll tales because I just don't like them but in this case, Esquinca strays away from the obvious and makes this one such a very human story that I couldn't help but be affected on a gut level. I also run from zombie-ish type things but "Tlatelolco Confidential" also defies stereotypes and injects the past into the present. After the 1968 student massacre at Mexico City's La Plaza de las Tres Culturas, la "convergencia de tres etapas importantes en la historia de México: la prehispánica, la colonial y la conteporánea," a small group of soldiers waiting for the bodies to be taken away experience something incredible -- thirteen of the dead students rise up, "bleeding from their mouths and baring their teeth" with the intention of attacking the soldiers. Firing on them again, the soliders succeeded in "re-killing" the students. Even stranger, when the crew came to take the bodies away, they counted twelve, not thirteen bodies, something one of them would later "swear on his mother" was true before noting that "if one of them was able to get back up and escape, there's a goddamn walking corpse loose in the city." Given the history of this location, perhaps something hungry may have been awakened by the blood flowing in the plaza that day. And finally, from my list of favorites is "Where I'm Going It's Always Night." Everardo, who is driving along the highway in a van, sees a guy with a backpack walking along the side the road, evidently not interested in hitchhiking, but he offers him a lift anyway. In exchanging the usual conversation, Jacobo, the passenger, tells the driver that he is a spelunker and a bounty hunter, retrieving bodies of cave explorers who'd for some reason or other had died during their caving experience, unable to get out. He's on his way now to do just that, heading to the mountains. Or at least, that's what he claims.

|

| from El Giroscopo Viajero |

Esquinca's stories are set in his native Mexico, and he incorporates his country's history, landscape and mythologies into his work, and bravo to James Jenkins for his excellent translation. At the same time, his subjects are definitely human, sharing much of the same anxieties and apprehensions as the author's readers outside the borders of his homeland. His work reaches depths that move well beneath the world we live in and uncovers hidden, unseen layers we don't see, as well as the small cracks in the universe that his characters don't know exist until they tumble into them. Even more so, he joins the ranks of my favorite writers whose work leaves me with the sense that the old ground has somehow shifted along with my understanding of how things actually are. The stories are fun with more than a hint of seriousness in what the author's trying to accomplish with them; they also acknowledge the influence of writers who came before him, as noted in the introduction, which you should definitely not miss.

All in all, a fine collection of stories by an extremely talented writer, and a book I most highly recommend, especially to people who, like me, love quality translated fiction that makes you think. It's downright creepy as well, aided by the excellent illustrations, so it's a book that will definitely appeal to readers of horror on the intelligent end of the spectrum.