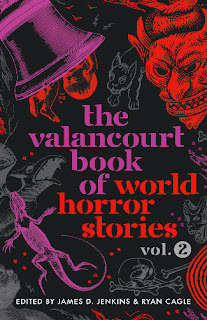

9781954321069

Valancourt, 2022

336 pp

hardcover, #19

(read in April)

There is a review of this book by Sean Guynes in the March 2022 issue of

World Literature Today where he writes that this

"... anticipated second volume is the after-party everyone wanted and more ..."

I'm including myself in that "everyone" because I hadn't even finished Volume One before hoping that Valancourt would do a second book, just like now I'm hoping that they will do a third. If that's not a recommendation, well, I don't know what is.

When the stories are as good as they are here, it's just plain difficult to single out a favorite, or even a group of favorites, but I'll try. Bora Chung's story "The Mask," a dark tale of obsession, addiction and the undoing of a man and his family and translated by Anton Hur (who also translated her fantastic Cursed Bunny) is in my top two, along with "The War" written by Wochiech Gunia from Poland. "The Mask" begins "with a noise" that seems to be coming from the ceiling of a couple's apartment, but above them is only the roof. On inspection though, the roof's steel door is not only locked but has a chain wrapped around its handles. The husband eventually gets up there with help from a boy he thinks has been sent by maintenance, and just before going back down sees a woman just standing there five stories up. She comes to him, and just as he reaches out his hand to her, she's no longer there. The roof noises stop but the wife later notices a dark stain that "had spread widely" on the wall in the master bedroom, accompanied by another noise that eventually she just tunes out. Her husband, who works nights and sleeps days, also encounters the stain -- and his life and that of his family will never be the same. "The War," translated by Anthony Scicsione is truly a masterpiece and I do not use that word lightly. This one I won't discuss here because it's one that absolutely needs to be experienced, but after reading in the editors' introduction to this tale that two of the author's "major literary influences" were Kafka and Ligotti, let's just say I was not at all surprised. I read this one twice, and it doesn't get any easier the second time. Another one that particularly stood out for me was Yasumi Tsuhara's "The Old Wound and the Sun," translated by Toshiya Kamei, which has more than just a touch of the surreal about it, concerning "a couple who died at the same time." A woman falls hard for a "twenty-something kid" from Ishigakijima, and rents a vacation house on the island where the two meet on weekends. Once things start rolling in the relationship, she finds not only that he's not all she thought he would be but also that he is haunted by the past. It seems he'd been in a fight at some point, leaving him with an old wound "from his navel across his abdomen to his side under his ribs." One night she wakes up to discover that even though there are no lights on, the room is "dimly lit;" on further discovery she realizes that the light is coming from his now-open wound. What follows is, as the narrator of this tale reveals, "bizarre, otherworldly and disturbing." The less said the better on this one. James D. Jenkins himself translated "Lucky Night," by Gary Victor from Haiti, which comes from a collection called Treize nouvelles vaudou (Thirteen Voodoo Tales, 2007), which is at this moment on a shelf in my house just waiting to be read. I can guarantee it won't be a long wait after having read this story. "Lucky Night" is the story of Kerou, who has climbed "the ladder from the lowly post of assistant mayor in a remote Haitian village," making his way into the Chamber of Deputies and now running for a seat in the senate. Throughout his political career, he has relied on the help of a certain Ti Pat, a "sorcerer" who tells him now that there is only one way to get the attention of "the forces" that would help him get there "without a fight." He must look for "a beggar in the vicinity of a cemetery on the night of a dark moon," and from there he has to "sleep with the beggar" or else his career is over. That is not an option for our senate hopeful who knows that once in office, his votes traded for cash would allow him and his family to "be free from want in this fucking country that he couldn't care less about."

In their introduction, the authors note that

"American horror writers have been using Haitian themes in their work for decades, from curses to voodoo dolls to zombies. But what would a voodoo-themed story look like if written by a Haitian author?"

Well, hats off to Gary Victor for letting us see firsthand. Rounding out my top five is writer Brazilian author Roberto Causo's "Train of Consequences" another story translated by James D. Jenkins. Sergio Lopes is journeying by train on the proverbial dark and stormy night, when he notices something weird. Although he thought he was in the last car, looking out the window he sees another behind him, and makes his way there to check it out. In a seat on the back wall he sees a man "who looked like a high-contrast drawing done in black and red" and that the car is filled with people smoking, "producing strongly scented crimson clouds. That's not the strangest thing -- it seems that the man and the passengers in that car know not only who he is, but also that he'd been part of a crackdown on guerillas in Araguaia during the period of Brazil's military dictatorship that he'd been involved in torture and "summary executions" and more. As he's told, they know "everything" about him, including the fact that Lopes is plagued by memories that he "can't get rid of." Expecting that "someone connected with his victims" would catch up with him some day, he's sure that blackmail looms, but he's assured that it's not blackmail but rather "more like a business deal" he's being offered -- a Faustian sort of exchange that will allow him to forget. The question is, what is his end of the deal to be? As the editors state, this is a story that is "as timely as ever," given Brazil's political situation.

The remainder of stories included here are also very well done, and my vote for most disturbing goes to two stories which were dark, gut-stabbing ohmygod tales. Don't get me wrong: the writing was great, but these two tales went well beyond my horror-reading comfort zone. These two, "The Bell" by Steinar Bragi from Iceland and "The Nature of Love" by Luciano Lamberti from Argentina, were the reading equivalent of putting my hands over my eyes during a truly discomforting horror film scene. These you can read without any hint from me -- first, you wouldn't believe me anyway, and second, I don't think I have the stomach to go back and reread either one.

With something for every horror reader, because after all, mileage does vary, Volume 2 showcases the work of twenty-one authors from twenty countries (Brazil is represented twice) which, according to the Editors' Foreword, were originally published in sixteen different languages. And M.S. Corley's illustrations are gorgeous, capturing in drawings some of the horrors found in this book. As much as I loved reading this anthology and its predecessor, in the bigger picture, the best thing is that these two volumes of horror fiction in translation even exist. I am a huge, huge advocate of works in translation, especially in the horror/weird genres which, unlike the books that make their way each year onto longlists for awards honoring translated literary fiction, seem to be extremely underrepresented. I would like to think things are slowly changing in this arena: last year I was over the moon happy when Tartarus published Nicola Lombardi's excellent The Gypsy Spiders and Other Tales, then came Bora Chung's positively mind-blowing Cursed Bunny published by Honford Star, which ended up on not only the longlist for this year's International Booker Prize, but the shortlist as well. So once again my grateful thanks to Valancourt for both volumes of World Horror Stories. Anyone who has read Volume 1 will definitely want to make this after-party; as I said on my initial reaction at goodreads, Valancourt has once again knocked it out of the park.

Very highly recommended -- and I will be among the first to order Volume 3. Hint hint.

ps/ Valancourt's international works can be found at their website

here.