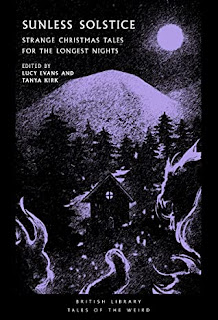

9780712354103

British Library, 2021

288 pp

paperback

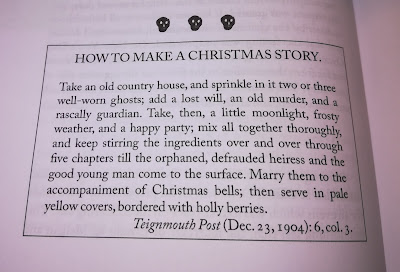

"Night, and especially Christmas night, is the best time to listen to a ghost story. Throw on the logs! Draw the curtains! Move your chairs nearer the fire and hearken!"

For me it's more a case of brewing some cardamom chai tea (with milk, of course), grabbing my favorite blanket, curling up in a cozy chair and opening a book, but I'd say the Victorians (in this case Frederick Manley) had it right: who wouldn't love to sit in the darkness with only a roaring fire for light and listen to a ghostly tale or two?

While there are only three stories from Victorian times in this anthology, they are three really good ones. Frederick Manley's "The Ghost at the Crossroads: An Irish Christmas Night Story" (1893) kicks off this anthology, finding a Christmas party in full swing at the "snug home" of the Sweenys in Derry Goland as the winds are howling outside. Just as it's time for the dancing to begin, with "the fun ... at its height," the revelry is interrupted by "the banshee's cry." It's not really a banshee, of course, but a young man with a story about a strange card game with a "thing in black." Definitely the perfect opener for what's to come, and the weirdness doesn't end there. Continuing on with the Victorians, there's Lettice Galbraith's "The Blue Room" (1897) which I've read elsewhere but still love, and last but not least, a story by American writer Elia Wilkinson Peattie, "On the Northern Ice" from 1898. Ralph Hagadorn is on his way to stand as groomsman to his best friend, getting a late start due to a delay caused by business. Skating across the Sault Ste. Marie region in the dead of night where "in those latitudes men see curious things when the hoar frost is on the earth," he suddenly realizes that not only is he not alone, but that the mysterious "white skater" is leading him away from his intended path. More than hints of the strange in this story, and we're not just talking about ghosts.

Of the next two stories, written in the 1920s, E. Temple Thurston's "

Ganthony's Wife" (1926) is completely new to me, while I'd previously read WJ Wintle's "

The Black Cat" from its original source,

Ghost Gleams: Tales of the Uncanny (1921), republished by

Sundial Press in 2019. Thurston's story, while beginning with the lament that "The custom of telling stories round the fire on Christmas is dying out," focuses on a ghost story told sitting "round a blazing wood fire" at a house party. The teller of the tale swears it's true, and that it's definitely not for children. Trust me, it isn't.

The 1930s are represented here with Hugh Walpole's 1933 story from

The Strand, "

Mr. Huffam" which quite honestly I didn't care for and Margery Lawrence's "

The Man Who Came Back" from 1935, which I very much enjoyed. I'm a true fangirl of any story with a séance at its heart; add in a medium's warning, a reluctant spirit guide and some "decidedly non-festive revelations," and well, you have a topnotch story here. I love Lawrence's work; in her lifetime she was, as the editors reveal, a "committed spiritualist" and member of

The Ghost Club; sadly she's somewhat underappreciated today, which is a true shame.

Bypassing the 1940s, "

The Third Shadow" by H. Russell Wakefield was first published in

Weird Tales in November 1950. To digress a moment, to my great delight because I'm a huge fan of the goat-footed god, the cover of that edition (above) features a Pan-like figure playing his pipe and cavorting in a forest, cloven hooves and all, with what looks to be a mountain range in the background. That would make sense as "The Third Shadow" is a tale centered around amateur mountain climbers. Told to an anonymous narrator by Sir Andrew Poursuivant as they sail to New York on the

Queen Elizabeth, it is the story of a man named Brown, "a master in all departments, finished cragsman and just as expert on snow and ice." It seems that Brown, in one of his reckless streaks, proposed to and married a woman named Hecate, who "made his life hell," and who was "a good deal heavier" than her husband. Two years after their marriage, Brown took Hecate to the Mer de Glâce glacier for a morning of training, during which her rope broke, sending her falling into a crevasse. Although he swears he'll never climb again, Sir Andrew reluctantly talks Brown into a trip up the

Dent du Géant, "a needle, some thirteen thousand feet high." It is a climb Sir Andrew says he will never make again because of what happened that June day. Following Wakefield is Daphne Du Maurier's "

The Apple Tree" (1952) which I've read more than a few times, and then there's a bizarre and rather creepy story by Muriel Spark called "

The Leaf-Sweeper" (1956) about a young man who wants to abolish Christmas and whose anti-Yule rantings land him in a mental asylum. But wait. There's more -- but I will say nothing about what happens next. Great story, actually, and a personal favorite.

Robert Aickman's "The Visiting Star" first published in 1966 (in Powers of Darkness: Macabre Stories) tops my list of favorites here. It is not the weirdest story I've ever read by this author (whose often-cryptic work I absolutely love) but strange it is all the same, employing here, as he often does, bits of the mythological, the psychological and just plain weirdness to tell the story of Arabella Rokeby, an actress who is set to make a return to the stage in a play she'd starred in years earlier in London, now being produced in an "unused and forgotten" theatre in some out of the way town. When "the great actress" arrives accompanied by her strange companion named Myrrha, Colvin (an expert on lead and plumbago mining), expecting an aging woman, is somewhat surprised by her youthful looks, but that's not the only strangeness to be found in this most excellent tale, a truly great choice by the editors for inclusion.

The closing story in Sunless Solstice is from 1974 by James Turner, from his collection of stories called Staircase to the Sea : Fourteen Ghost Stories. I've looked for this book everywhere and sadly, I can't find a copy anywhere. In "A Fall of Snow" Nicky, a boy from Cornwall, is staying at his uncle's farm in East Anglia over the Christmas holidays while his parents are in New York; the arrival of snow both awes and terrifies him. Why this is so I will not say, but a toboggan ride with his cousin heralds the unexpected and the strange.

As is the case with the other books in the British Library Tales of the Weird series, it's a true delight reading the work of past masters of the strange. The editors of Sunless Solstice have certainly done their research in putting together this book, leaving their readers with enough scary chills and weirdness to take them through the Christmas holidays, but as always, you don't need to limit yourself to the season to find joy in the reading. Very nicely done, and of course, definitely recommended.